It’s a bustling Saturday at Boulangerie Carlota, and there’s a steady stream of customers, all smiles as they look upon a counter laden with baked goods: Rollos de guayaba with dizzying layers of pastry curled around cream cheese and pink guava curd, fluffy concha buns with a crackled, shell-like topping, and focaccia flecked with hibiscus petals and oregano.

But these days, the star is the pan de muerto.

Pan de muerto, as its name implies, is baked and eaten around the Mexican holiday of the Day of the Dead, el Día de los Muertos, a festival so significant that it is recognized on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Join The Main free and keep reading.

Create a free account.

Create a free account to unlock this story and get 3 articles a month, plus our weekly Bulletin.

- 3 free articles per month

- Save your favourite places & guides

- Weekly newsletter The Bulletin

- Stay connected to Montreal culture

Become an Insider.

Unlock unlimited access, exclusive guides, and member perks — and help support the independent Montreal stories we publish every week.

Subscribe- Unlimited access to all stories

- Exclusive features & local insights

- Special offers and event invites

- 10% off in our shop

- Support local storytelling

Already a member? Sign in

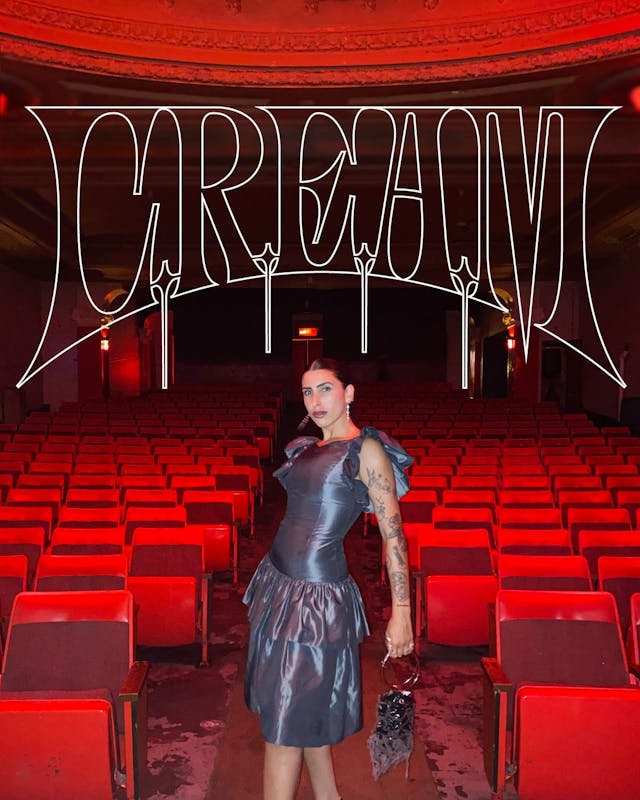

![The Bulletin: Cold raves, beer memberships, and film festivals galore [Issue #164]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fthemain.ghost.io%2Fcontent%2Fimages%2F2026%2F01%2Fericbranover_1765408527_3784843508759209075_31339819-1.jpg&w=256&q=75)

![The Reeds: A Novel [Stamped by Author]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.shopify.com%2Fs%2Ffiles%2F1%2F0601%2F1709%2F0544%2Ffiles%2FIMG_9098.heic%3Fv%3D1730301494&w=3840&q=75)